Last month I went to Swift Creek Bluffs to see if I could find some salamanders to photograph. I don’t have much experience with salamanders, so I did not have much luck. I knew they layed their eggs in ephemeral pools. These pools dry up in the summer, so there are no fish to eat the eggs. I found lots of egg masses in the pools but did not find any salamanders. I spent the rest of the morning photographing wildflowers and ferns and then headed back to my truck. I often run into people I know here, and this time I bumped into “Rock” Turner. With a nickname like “Rock”, you might expect him to be either a brute or a geologist, but this guy loves reptiles and amphibians. You have to put his nickname together with his last name to get the joke. Oh, and you have to know a little about what is involved in finding these sorts of critters.

When I saw Rock I thought, “this is my chance!” I asked if he could help me find some Salamanders. He agreed with his typical enthusiasm. We found several slimy salamanders, but they did not want to be photographed. Then Rock came up holding a salamander egg mass. I had seen them just beneath the surface of the water earlier, but I never tried picking them up. Out of the murky water it was easy to see lots of interesting details and color. Looking into this jiggling mass of gelatin in Rock’s hands was like looking into another universe. I had Rock hold the egg mass in the sunlight as I tried to make a photograph. He did not get his nickname for being “rock” steady, and every little body movement was making the egg mass jiggle. He had to hold his breath and brace his arms against a log to try and stop the egg mass from jiggling. After a bit of effort, I was able to make a sharp photograph, but because I was looking down into his hands, I was not able to get rid of the sky reflected on the surface of the egg mass. Still, I liked the idea of the photograph and decided I would come back another day after I figured out how to solve the sky reflection problem.

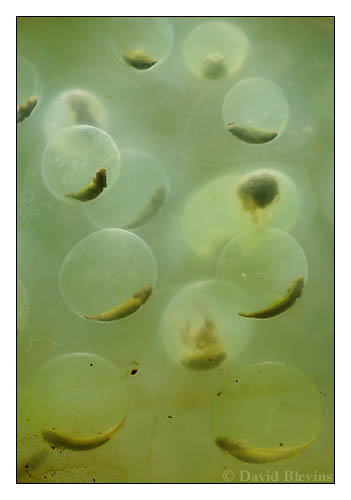

Spotted Salamander Eggs

I came back about a week later thinking I would be able to do something similar and block the sky reflection. That trip was a total bust; nothing I tried would completely eliminate the sky reflection. I just could not get the image I wanted. I wanted the image to feel like you were in amongst the salamander eggs, like being in another universe. But as long as you can see the reflections on the surface of the gelatin, it gives you the impression you are on the outside looking in. Then I remembered the miniature aquarium I built.

Back in 2002, I was making photographs to tell the success story of the salmon habitat restoration work of the Alouette River Management Society. I wanted to make photographs of the young fry in the river as part of that photo essay. I spent a lot of time chasing those little fry with my camera under water, but they were just too small and fast to make a decent photograph. To solve the problem I built a small aquarium designed to keep the fry within the depth of field of my macro lens so I could get an up-close and detailed photograph. This little aquarium was made out of two 4 inch square pieces of glass and a piece of metal strap used to bundle lumber. I attached it all together with silicon adhesive. It cost me nothing to make since I had all these materials lying about. It worked great; the only difficult part was catching the fry. This photograph, by the way, has been published more than any of my other images.

Anyway, I realized that if I put the salamander egg mass inside the aquarium, I could shoot horizontally rather than down and eliminate the sky reflection problem. Also, by pressing the gelatin up against the glass, it would eliminate any hint of the surface of the gelatin and give the impression of being inside it.

Spotted Salamander Eggs

The last piece of the puzzle was the lighting. The ambient light was too soft and did not provide the high contrast I had seen that first day with Rock. I tried several different flash setups and decided the one I liked best was one flash from directly above. This gave the eggs a strong spherical shape and helped define the bodies of the young salamanders.